Written by Matt Duffy, Carex President

What the hell is going on with the Labor Market?

Specifically, what’s happening with the monthly job creation reports? Last week’s July jobs report dropped – and just hours later, Trump fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Since then, I’ve received more than 50 texts from friends, family, and colleagues weighing in on the subject.

Let’s rewind a bit.

Last month, the U.S. economy added just 73,000 jobs. On its own, that number is soft, but not especially alarming. What is alarming, however, are the revisions to May and June: the job counts for those two months were revised down by a combined 258,000, to just 19,000 and 14,000 jobs, respectively. That makes June’s job growth the weakest in more than four years. As a result, the three-month moving average has fallen to just 35,000—a level not seen since 2020 and one of the weakest in the past five years. To be clear, revisions aren’t unusual. Around this time last year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed that 818,000 fewer jobs had been created over a 12-month period than originally reported. But revisions of this magnitude over such a short window are rare – and troubling. This signals a shift in the narrative: from a resilient labor market to one showing increasing signs of fragility.

These revisions were the catalyst for firing the head of the BLS. For more context, you can read Carex’s August 2025 Labor Market Insights Report.

So, what do I think?

I have thoughts – but I’m not bold enough to say whether Trump’s move was right or wrong. In life, there are a few things I’m certain of: mountains are beautiful, surfing is magical, and yes, the Bears still suck. There are also many things I think I know – geometry, the meaning of the Sopranos finale, and how the BLS compiles its data. Since I write a monthly Labor Market Insights report, it would be strange not to address the recent chaos. I’ll try to steer clear of the politics and instead break down how the data is collected and why revisions happen.

The role of the BLS

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, founded in 1884, is the oldest of the federal government’s 13 statistical agencies. Its job is to give policymakers, business leaders, and armchair economists like me accurate and timely labor market data. But those two goals – speed and accuracy – can be in tension. To balance the two, the BLS releases its monthly jobs report just days after the month ends, then revises the numbers twice in the following months as more data rolls in. Erica Groshen, who led BLS for 4 years recently stated – “when a statistical agency revises its data, that is an indication it cares both about timeliness and about accuracy.“ It’s saying: ‘We’re going to get you something in a short period of time that we think contains valuable information using methods that are well-tested. However, it’s not going to be as good as the revised data we’ll have in a month or two.’ So, revisions are not a bug, they are a feature of the program.”

Where do the job creation numbers come from?

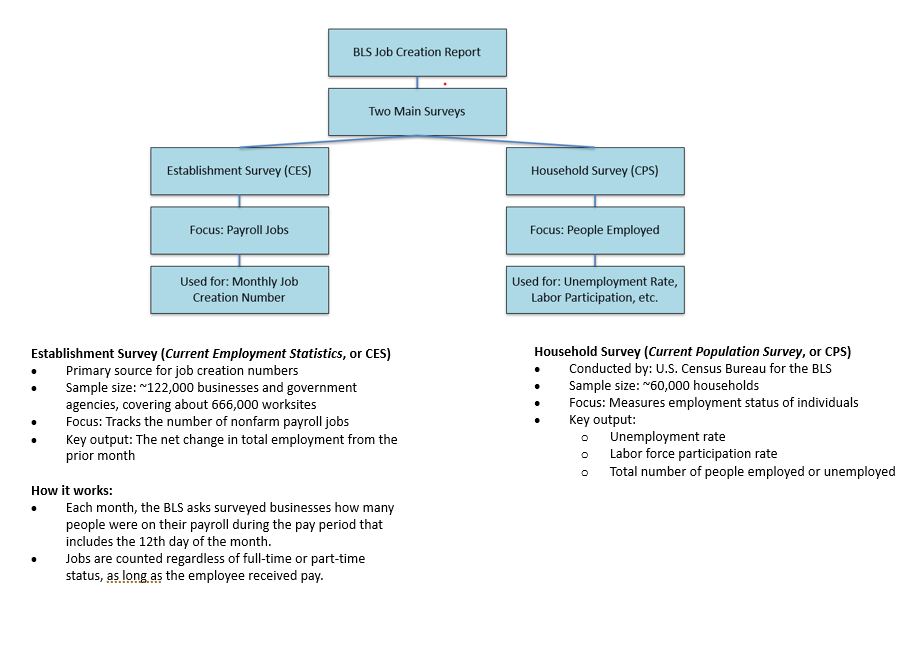

The BLS uses two major surveys:

- CES (Current Employment Statistics) – This payroll survey captures job creation numbers (the left-hand side).

- CPS (Current Population Survey) – This household survey is where we get the unemployment rate and other labor force metrics (the right-hand side).

So, what’s up with the revisions!?

Both surveys have their issues. The CES has a standard error of ~100,000 jobs, meaning any reported monthly change within that range isn’t statistically significant. And reporting is voluntary, which means many companies miss the submission deadline. Sometimes it’s because HR is on vacation, they simply forget, or they just don’t feel like it. It happens. Keep in mind, this is voluntary – and responding to government surveys likely isn’t their top priority. Another issue might be staffing levels. The agency has reportedly lost more than 15% of its workforce through attrition and has been under a hiring freeze since January. That kind of capacity reduction could be contributing to the increased volatility in recent data.

An antiquated but consistent process

The survey process, sample sizes, and methodology are outdated—there’s no denying that. The BLS has been slow to modernize. But the methods are at least consistent, and over time, the data does reveal meaningful trends.

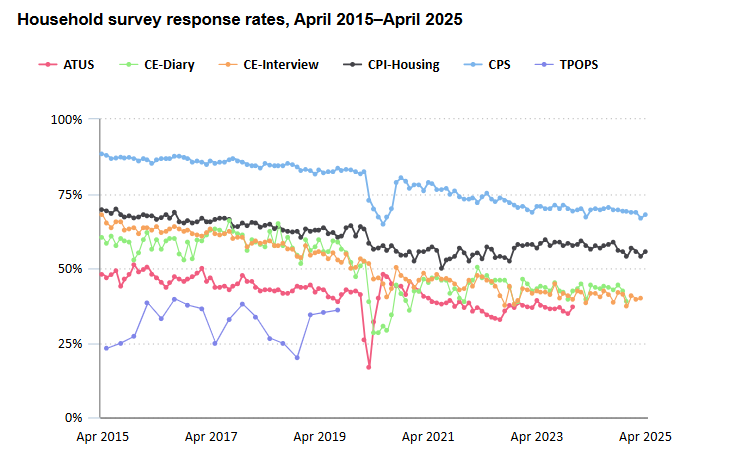

The bigger issue, in my view, isn’t the math. It’s participation. Response rates for both the CES and CPS have been declining for the past decade. If people begin to believe that labor data is being manipulated – either now or by future administrations – they may opt out altogether. That poses a serious risk to the reliability of labor market data moving forward. If trust erodes, so does the foundation of this data-driven system. And once we lose faith in the data, it becomes exponentially harder to rebuild.